Cover image used by permission: Copyright © 2021: Sara Stathas. All rights reserved.

In this first of two posts, we will build the case that Pebble Dash was not a distinctive feature of Frank Lloyd Wright’s American System Built Homes. It was someone else’s idea.

The original Pebble Dash surfaces in the sleeping porch of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Elizabeth Murphy House — and other remnants and re-creations of Pebble Dash on other extant American System-Built Homes — have become architectural lore among Wright-o-files. Most visitors to this tiny home gasp when they see it. It feels both rock-solid and also fragile. Natural and unnatural at the same time. Sparkly and also cold and grey. Visitors are both curious and skeptical. To many, it doesn’t seem right that this is a Wright idea.

What is Pebble Dash? The name explains. Instead of stucco on a building exterior, pebbles are dashed onto still-wet plaster. Here is a video of the process:

ASBH aficionados know that Pebble Dash occupies much of the tour agenda of the restored model B-1 near 16th and Layton. Docents explain that Pebble Dash was appealing when new, but didn’t weather well – soaking up dirt and dust and decaying fast in harsh Wisconsin winters. Indeed, all the Pebble Dash on all the Burnham homes was covered with siding or paint within about 15 years. Tour-goers are left with the sense that Wright had been careless with his Pebble Dash choice.

Was Pebble Dash another example of Wright pushing limits; of the genius, futurist architect experimenting with untraditional materials and methods but not always succeeding? Did he intend for the tiny quartzite and biotite chips to shimmer and dance like some starry night? Was this another way of bringing nature to the American living experience?

Image Courtesy: Shorewood Historical Society

Indeed, while the physical evidence suggests that Pebble Dash probably covered every constructed ASBH, the documented evidence tells us that Pebble Dash was an alternation of Wright’s designs — something he didn’t agree to and hoped to cover up and forget about, when he sued to cancel his agreement with his partner-builder Arthur Richards in 1917 and ended the ASBH program altogether.

Consider these facts:

- Pebble Dash doesn’t appear on or in any other known Wright design.

- The words Pebble and Dash do not appear anywhere in Wright’s written specifications for his American System-Built Homes (ASBHs) or anywhere in the drawing archive.

- A reading of the ASBH archives reveals that Wright’s early design concepts include at least two exterior treatments: horizontal board and batten and stucco (click to see examples). Initially, he seemed to favor board and batten, creating more of these renderings than others. Often the same home was drawn with more than one exterior surface. As the portfolio expanded and matured, he shifted his preference to stucco, but he may been toying with choices to offer to clients and to mix and match designs within neighborhoods.1

- In 1915, Arthur Richards purchased the designs for three of Wright’s models to build prototype ASB homes on Burnham street on Milwaukee’s south side. His builders applied Pebble Dash on the buildings, despite Wright’s drawings and notes calling for stucco.

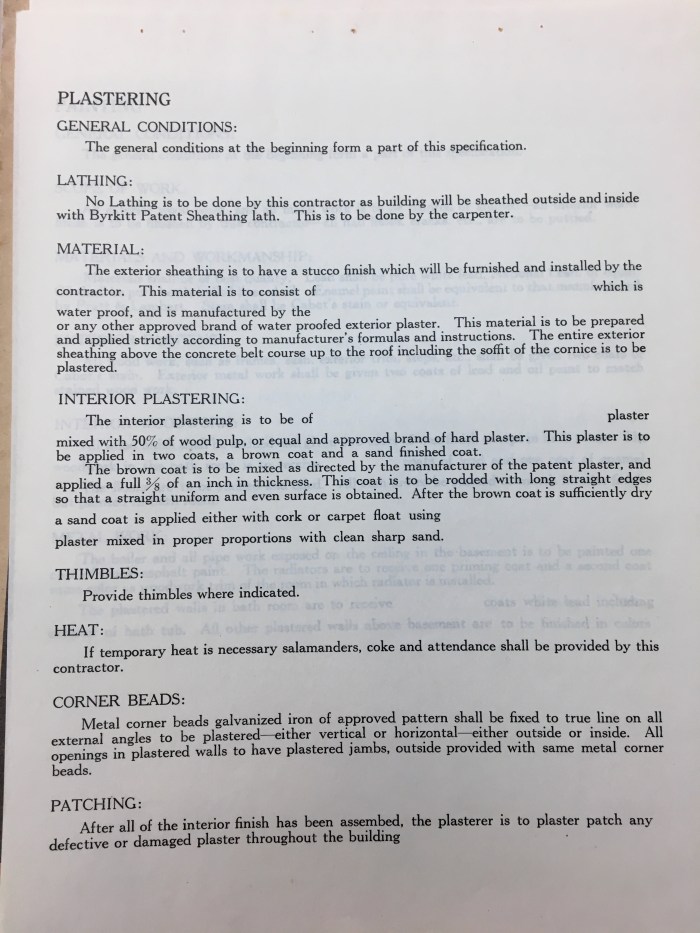

- Wright’s written instructions for commercial ASBHs built after the Burnham houses calls for a stucco finish manufactured by an approved brand.2 Specifically, the specification reads:

- In 1916, Richards and Wright partnered to promote ASBHs in the North America and Europe. Wright would design and Richards would sell and supply. Before sharing one of Wright’s renderings with a prospective client, Richards would often make notes in the margins calling out a texture he called “stipples”, specifying the colors that would be used, including “light, medium and dark gray.”3 Richards’ references to stipples are proxy for Pebble Dash.

- Most ASB Homes sold and built under their the 1916 contract featured Pebble Dash in colors consistent with Richard’s notations (another example shown below.)

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives : architectural drawings, ca. 1885-1959. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

All this is to say that Richards, not Wright, was the proponent of Pebble Dash on ASBHs. For this, we will claw back less-informed claims in previous posts, like this one. But it also leaves us with many questions:

- Was Pebble Dash a source of disagreement between Wright and Richards?

- Why did Richards seem set on it?

- Did Wright make his views about Pebble Dash known?

- If one were to restore an American System Built Home today, would it be more appropriate to clad it waterproof plaster or rough, sparkly pebbles?

- And if pebbles, where would they need to come from for maximum authenticity?

Look for Part 2 for these and other answers in the next weeks.

– N. Hayes, December, 2025

- Wright, Frank Lloyd (American architect, 1867-1959), and architects. American System-Built (Ready-Cut) Houses for The Richards Company. Unbuilt Project. 1911. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University; Avery Drawings & Archives; Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives : architectural drawings, 1885 – 1959. Frank Lloyd Wright Drawings (Reference Photographs). Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.28510187. Accessed 23 Dec. 2025. ↩︎

- Specifications of Materials and Labor Required for the American Model ____ in Accordance with Drawings Prepared by Frank Lloyd Wright, Architect,” FLWFA Specs Box 2, 1112-1903, Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, Museum of Modern Art, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York. ↩︎

- Wright, Frank Lloyd (American architect, 1867-1959), and architects. American System-Built (Ready-Cut) Houses for The Richards Company. Unbuilt Project. 1911. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University; Avery Drawings & Archives; Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives : architectural drawings, 1885 – 1959. Frank Lloyd Wright Drawings (Reference Photographs). Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.28510315. Accessed 23 Dec. 2025. ↩︎

One thought on “Pebble Dash was not Wright’s Idea (Part 1)”