In a prior post called “Why did Frank Lloyd Wright Keep the Drawings he Planned to Forget?”, I wrote about how Frank Lloyd Wright’s American System-Built Homes (ASBH) portfolio survived fire and calamity when many other Wright works were lost. The post raised some Wright-o-file eyebrows. I was advised that “a genius saves everything.”

However, Wright’s cancellation of the ASBH program and people was ruthless. He directed his lawyer to “erase” it. No matter how much he loved his work, he did his best to make it disappear (while taking historians off the trail for almost a century.)

Indeed, Wright’s decision to stash the drawings was more practical than egotistic: Wright believed that Arthur Richards and Russell Barr Williamson had plans to build American System-Built Homes without him and he sued to stop them. The Court found in his favor and the ASBH drawings, included supporting evidence, were returned and squirreled away as protection against future theft.1 (We’ll do a deep dive on this evidence on March 17, at NSSS. More information about that event is here.)

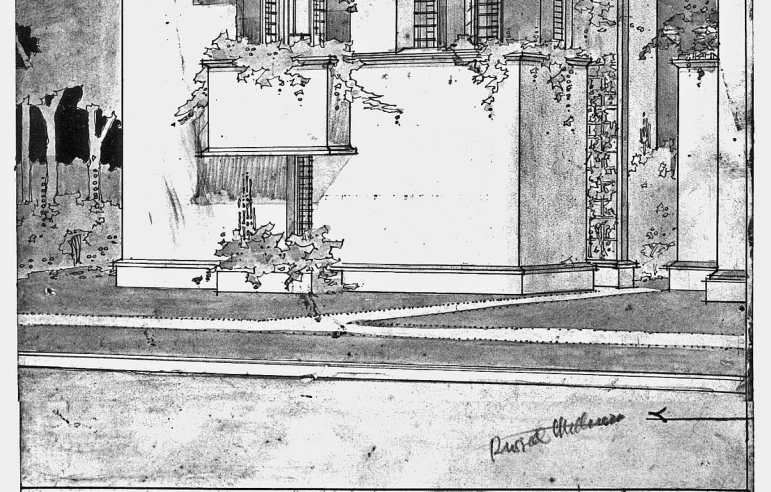

Wright’s plan succeeded. While Richards continued to promote homes in the Prairie Style with Williamson as his new design partner; Wright’s ASBH key ideas and innovations were substantially altered by Williamson – some have said homogenized – to avoid legal jeopardy.

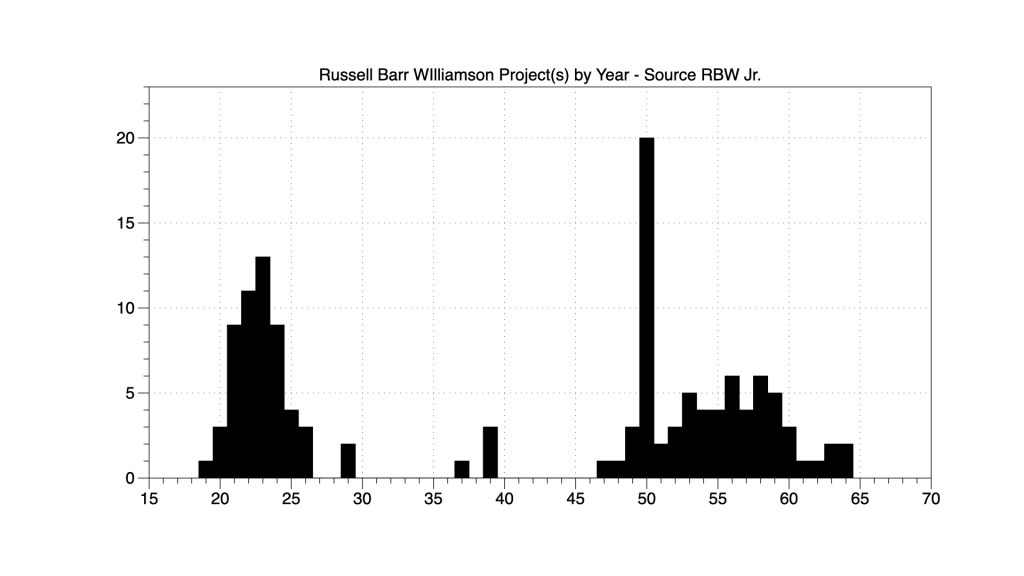

The records of Williamson’s ASBH alteration work did not survive. His family reported that he destroyed all of his records from before 1929. Ironically, there are more Williamson drawings from four years in Wright’s employ, than there are Williamson’s own work in the following twelve years. Why?

A practical answer is emerging, again, from legal weeds. The Roaring 20s – at least the early part of the 1920s – roared for Williamson. Early in the decade, he was busy designing and building homes all over southeast Wisconsin. Alongside Richards, he saw more opportunities than just design work: he could finance, he could invest, and he could speculate, and he did it all well. In less than 10 years, he completed over 54 sometimes opulent projects, including his own home in Whitefish Bay. He was flush with cash and had built a powerful local brand.

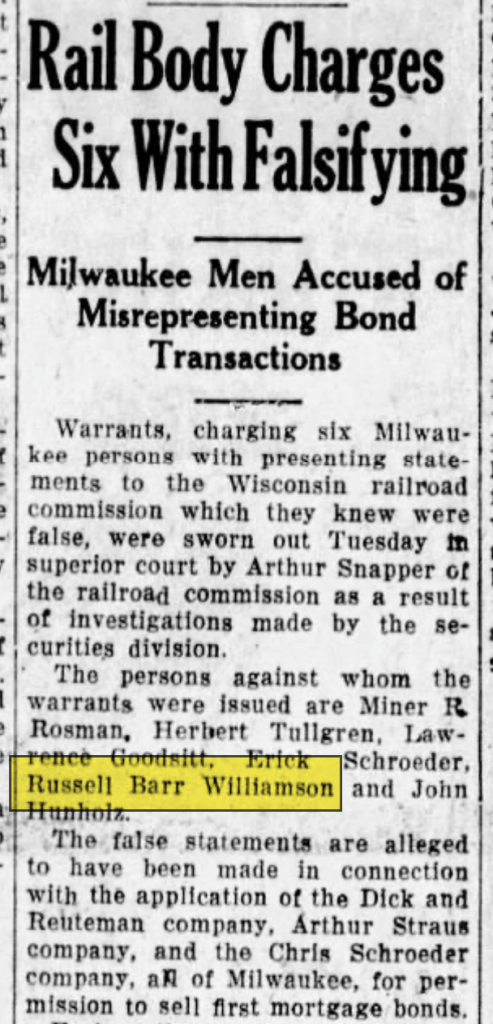

Things began to unravel in July of 1927, when Williamson – along with a cohort of fellow-developers and financiers – was arrested for having “padded” costs to inflate mortgage bond values. It was a sign of over-exuberance in real-estate circles. It was also illegal.

But arrest didn’t slow Williamson, who had tasted wealth and fame and wanted more.

I have written about the unbuilt “skyscraper” that bankrupted Williamson when markets crashed and the Great Depression began.2 It was to be his most impressive project yet. Instead, his timing was terrible and the project failed before launch. He had borrowed against, leveraged and lost his home and practice and didn’t have another decent commission for almost 20 years. The project was so damaging to Williamson’s career that he never mentioned it to his kids, despite moving into a small apartment, gifted to him by his friend Richards, and where the kids were raised.

Together, these events set Williamson back decades. For some of that time, he may have thought he was done with architecture. And that is why he didn’t save his early drawings.

-Nicholas Hayes, February 2026.3

- Frank Lloyd Wright Vs. The Richards Company, a Wis corp. and The Richards Company a Delaware Corporation, Dane County Circuit Court Case Files, Dane Series 109, box 386. Source: Wisconsin Historical Society. ↩︎

- “To Break Ground for Shorewood’s First Skyscraper,” Lake Shore Radio I, no. 29 (February 8, 1929.) Shorewood Historical Society. ↩︎

- Image Used by Permission. Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives: architectural drawings, ca. 1885–1959. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). ↩︎