Also, where does one get raw Magnesite before 1917?

In our recent post on Pebble Dash, we shared evidence that it was Arthur Richards, Wright’s partner-developer from 1916-1917, who decided to cover the American System-Built Homes (ASBH) in pebbles, not Frank Lloyd Wright. This might land as a surprise to students of the ASBH program, who often assume that Pebble Dash was a Wrightian materials-experiment gone wrong.

Let’s look deeper.

Under the terms of their agreement, Richards had contractual responsibility for selling Wright’s ASBH designs and then providing all of the materials (concrete, lumber, plaster, hardware) for homes to be constructed. The partners were looking for efficiencies to keep prices and costs low. Wright surrounded the spaces with windows, adding light without adding expense. Richards, meanwhile, invested in materials and tooling that would support the scale and speed. He would buy in bulk and ration quantities to the job sites to minimize waste. This is what he did with Magnesite, the crushed rock dashed on the ASBH exterior surfaces.

Magnesite is a mineral that occurs in the seams of magnesium rich rocks. In its raw form, it can be crystalline and semi-translucent and ranges in color from white to gray to tan and black. Here it is in our sleeping porch.

However, when Magnesite ore is heated to a high temperature, it loses structure and becomes inert, making it useful as a fire resistant agent in refractory bricks for ovens, among other applications. It turns from rock to powder. To this day, most Magnesite is mined and then burned to make bricks for industrial ovens like those used to make steel.

Wright was an early adopter, using calcined (burned) Magnesite in cement floors and other features of buildings like the Larkin Administration Building in the late 19th century.1 About it, he said:

“The floors and interior trimmings … … have been worked out in magnesite, a new building material consistently used for the first time in this structure. Stairs, floors, doors, window sills, coping, capitals, partitions, desk tops, plumbing slabs, all of this material… are finished hard and durable as iron. [They are] made fireproof with magnesite.” – FLlW.

As a developer, Richards would also have known about Magnesite from local suppliers promoting new uses in construction. Milwaukee’s Forrer-Pipkorn Company was actively promoting “Magnesite-stucco” to area builders during the time Richards was using it.2 Magnesite stucco, unlike its lime counterpart, could be applied in freezing temperatures. The material went up quickly and in all kinds of weather, without needing special skills or tools to apply.

Importantly, there were two uses of Magnesite in the American System-Built Homes, despite the fact that Wright didn’t call it out in the specifications.

1.) During the work to restore Wright’s ASBH Model B1 on the Burnham Block in Milwaukee, forensic archeologist Nikolas Vakalis found calcined Magnesite in the original exterior stucco of the home.3

2.) Vakalis may have seen, but didn’t report, that raw Magnesite ore crushed to pebble size had been dashed onto that wet Magnesite stucco.

In fact, during the restoration of the ASBH Model B1 on Burnham Block, the source of stone for pebble dash was a mystery. A search for a comparable mineral composition came up empty. Indeed, there were no Magnesite mines in the Midwest in 1915 (and there are none, still.) The Magnesite stucco and the pebbles embedded in it had to have come from the same far-away source, and arrived having been processed differently.

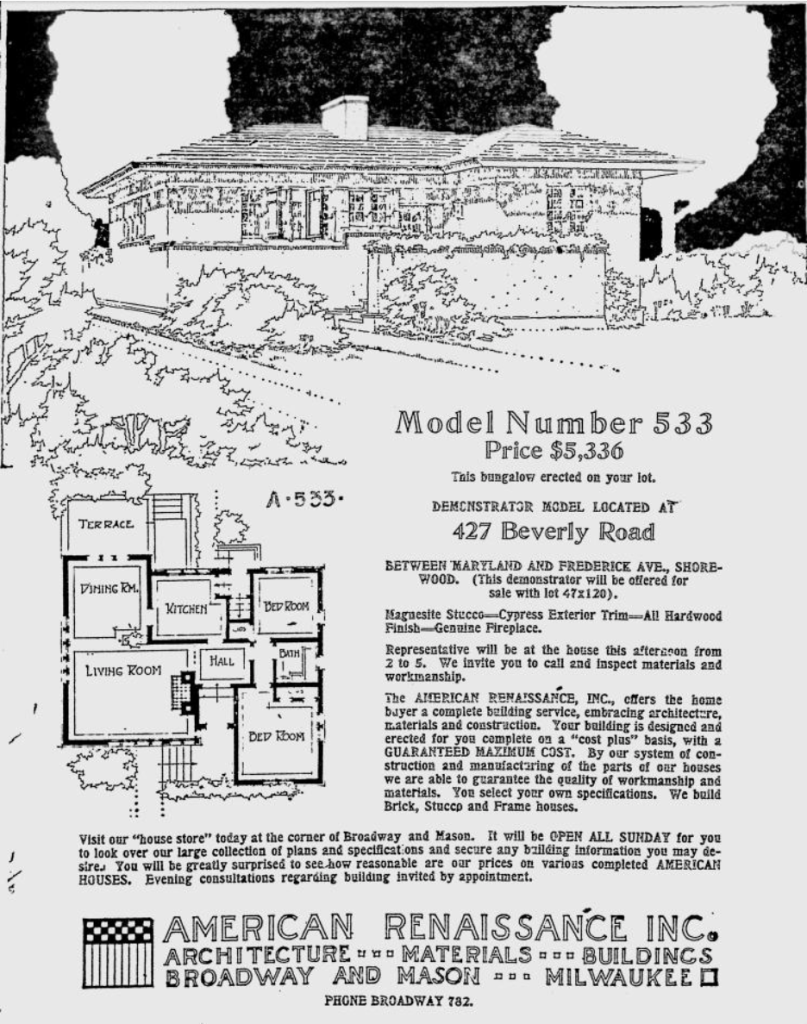

Fast forward to 1918 when the ASBH program had been cancelled by Wright. Richards needed to work down his overstock of Magnesite by building and selling homes under other brands. In a 1919 advertisement to sell a home on Beverly Avenue in Shorewood, Wisconsin (only a few hundred feet from The Elizabeth Murphy House), Richards promoted the idea of “Magnesite Stucco”, drawn here by Russell Barr Williamson with “stippling” on the exterior, like the surfaces seen on Frank Lloyd Wright’s ASB Homes.

Another home about twenty blocks west on Keefe Street in Milwaukee features Pebble Dash identical to that found on ASB Homes, though in rough condition. This example is near where Richards’ Lumber Yard had stashed tons of pebbles to be dashed and the stucco to dash it on.

It should be noted: Pebble Dash is hard to spot. Often, it has been overpainted and looks like conventional stucco. When it fails catastrophically, modern siding hides it. There are only two known undisturbed ASBH examples remaining.

Finally, there is the question of the origin of Richards’ Magnesite. Where did it come from?

According to government witness Robert W. Page, President of the Marbleoid Company of New York, no US (or North American) sources for stucco-suitable Magnesite existed before World War 1. Mr. Page was among building material suppliers petitioning Senators in 1919 to NOT apply tariffs on imported Magnesite. Witnesses told the committee that all the Magnesite used in stucco applications before the United States entered WWI came from the mountains of Northern Greece, and was processed either in Holland, Germany, or on Long Island. That supply had been interrupted in 1917 by World War I, and US importers hoped to rebuild the supply chain following armistice, since fledgling North American production could not meet the demand or the quality required for building construction.4 (A few test mines had come online in Washington State, California and Mexico to supply refractory bricks for steel-making, but domestic Magnesite did not have the uniformity to be calcined for use in stucco plaster.)

Wright also knew of the Greek supply of Magnesite as an alternative to Portland, or lime-based, cements. About his Larkin building, he said:

“The magnesite interior trimming throughout the structure was… … from the magnesite mines of Greece direct to the building… at less cost than another permanent masonry material.” – FLW5

Why Wright called for “any approved brand of water proofed exterior plaster” for ASBHs, and not Magnesite, remains a mystery.6

Still, Richards purchased his lot of Grecian Magnesite in 1915 to build the ASBH prototype Burnham block, perhaps from the Forrer-Pipkorn Company, and had enough to build dozens more ASB Homes and a few more Pebble Dash homes after Wright cancelled the ASBH program. We expect he bought at least two full train cars shipped from Long Island for about $25 dollars a ton: one with calcined Magnesite for plaster, perhaps with Wright’s nod, and the other with raw rock for pebbles, despite Wright’s orders.

So this is Greek rock on and in our tiny Wright-designed, Richards-supplied home. My Greek mother will be pleased. Wright, not so much.

-Nicholas Hayes, January 2026.

Image Credit: Sara Stathas.

- Frank Lloyd Wright 1867-1959, Essential Texts, edited by Robert Twombley, W.W. Norton and Company, 2009, Pages 74-75. ↩︎

- Building Supply News and Home Appliances, July 4, 1922, Vol. 12, Number 1. Contractors Praise Dealer’s Policy. Retrieved January 2026. ↩︎

- Vakalis, Nikolas. House B-1 American System-Built Homes – Restoration of the Finishing. (Technical Research and Specification Report, February 2006). Source: Wisconsin Historical Society. ↩︎

- Sixty-Sixth Congress, Hearings before the Committee on Finance, US Senate. H.R. 5218, A Bill to Provide Revenue for the Government and to Establish and Maintain the Production of Magnesite Ores and the Manufactures Thereof in the United States, December 6, 1919. Retrieved January 2026. ↩︎

- Frank Lloyd Wright 1867-1959, Essential Texts, edited by Robert Twombley, W.W. Norton and Company, 2009, Pages 74-76. ↩︎

- Specifications of Materials and Labor Required for the American Model __ in Accordance with Drawings Prepared by Frank Lloyd Wright, Architect,” FLWFA Specs Box 2, 1112-1903, Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, Museum of Modern Art, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York. ↩︎